h2>Dating : Another Bloody Mosque

There’s a certain point any European tour group reaches, and it’s called ABC.

Another Bloody Cathedral!

Yes, after a while they all blend together, no matter how historic or grand or beautiful they are because every day the tour coach stops in a city, and we look at the famous sights, and the cathedral is a must-see.

In Iran, not so many cathedrals — though there are one or two, and Christians are allowed altar wine in this notionally alcohol-free land — but there are plenty of mosques, as we discovered in exactly the same fashion by visiting as many as the itinerary would allow.

There are the grand Friday mosques, some of the iconic, brilliant in their architecture, impossibly over-decorated, airy domes above columns and squinches, calligraphy precise and exquisite in tilework, full of gawking tourists photographing everything in sight.

Sometimes we women were required to wear chadors on top of our regular hijab, and tourist versions in floral prints were distributed before entry. We all photographed each other in our thin cotton finery, of course. This was the real Iran!

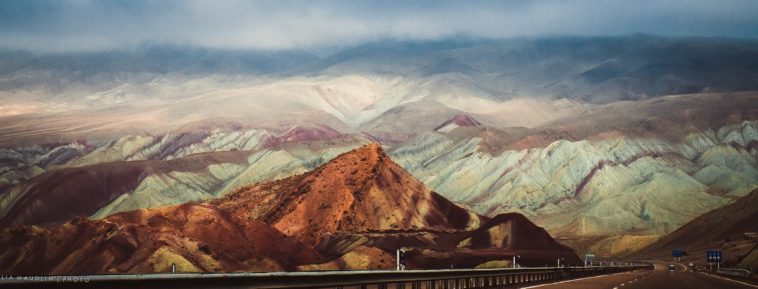

Then there were the regular suburban mosques, and Iran has about a bazillion of them. And along the sides of the motorways linking the cities — Iran has a highway system that is the equivalent of the American Interstates — there would be truck stops, each with a tiny mosque, dome about as big as a family size pizza, and minaret towers only a Barbie doll could climb.

“Those,” said our guide, who was an old Persian hand, “are called mosquitoes.”

A land of beauty

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a more beautiful religious site than the Shah Mosque in Isfahan, which is itself a glorious city full of grand civic architecture dating back centuries. Inside the mosque, no expense was spared at decoration, and it shows.

Well, a little expense. In the tilework by the door, there are some multicoloured decorated tiles. One section has sublime colours, deep and rich. We were told that the pigments had to be fired to an exact temperature; different temperatures for each hue, and then the tiles would be cut precisely and fitted together to make the finished pattern.

The shah had inspected the work and admired the quality. How long, he asked, for the work to be complete?

“It is painstaking and time-consuming work,” he was told, “And you have commissioned such a huge building. For the entire interior, about a century.”

“Well, I’m paying for the building, and I want to see it complete. Find some way to do it quicker!”

So the craftsmen painted their patterns on the tiles, and they were fired to a temperature that was pretty good for all the various colours. Not perfect, but it did the job, and the Shah got to see his creation finished before ascending to another plane.

The land itself, beyond anything that mankind can create, is full of grand beauty. Tehran sits at the foot of a range of snow-capped mountains. Jagged peaks, rolling deserts, great rivers, and vast panoramas abound.

The cities are full of parks, whimsical artworks, ancient buildings and new tourist hotels in the Russian style. And friendly, cheerful people about as religious as we Australians.

Which is to say, not a lot.

A mosque in Zanjan

Not a grand Friday mosque, nor a tiny truckstop affair, not even a building with a dome and minarets.

In the middle of the old city, not far from the bazaar, we were guided into a nondescript building, maybe once a shop, or a school, or a restaurant.

Just a mosque in a big rectangular room, with old carpets on the floor, gifted to the mosque by families who had no further use for them. A bare wooden minbar — the Islamic pulpit — and that was about it.

None of the intricate tilework, soaring architecture, and lavish decoration of the famous mosques.

This was a room that was earth-toned, from the natural pigments of the threadbare carpets to the dark wood of the walls, and the thick drapes dividing the women’s section from the body of the main room.

Our young Iranian guide sat on the minbar steps and told us about day to day Islam. The prayers, the little buttons on which the faithful rest their foreheads, the traditions, the symbols. Not much of a mosque-attender himself, he turned up for the celebrations of family rituals, much like Australians might show up for weddings, christenings, and funerals, and the odd Christmas service.

But this mosque, like most suburban mosques, had its regular worshipers. The young people of Iran — and it is a young population, due to the Iran/Iraq war — may not be regulars, but their parents and grandparents, and the most devout of their peers attend regularly.

I could feel it. Strange how these places develop their own human glow. The invisible congregation had blessed this unremarkable room with their prayers, their devotions, their spirit, and while I may not have been a believer, I could appreciate the way that they, like humans around the world, had found a way to celebrate the magic of the creation and the light of human consciousness.

Another bloody mosque

This room, blessed by the daily and weekly devotions of its regulars, was in my thoughts recently, with the sentencing — life, without the chance of parole — of the man who murdered fifty-one worshippers in two Christchurch mosques in 2019.

That came as a shocking blow. To me, to New Zealand, to all who love peace and tolerance.

Christchurch is possibly the city I love most in the world. I have fond memories of love and lovers, strolling through its botanic gardens, along the banks of the River Avon, across its Cathedral Square. Old buildings, historic streets, suburbs with the gabled roofs and stone churches of England, transplanted to the antipodes.

The earthquake of 2011 destroyed many of those buildings directly, and later as those rendered unsafe were demolished. The spire of the cathedral tumbled down into the square, and nearby office buildings pancaked, crushing those insides. 185 people lost their lives, and many more were forced to leave their homes.

And then eight years, this recovering city was hit by an act of terrorism, with peaceful residents murdered at their prayers.

The main city mosque, on the edge of a lovely urban park, was attacked during the Friday prayers. 44 worshipers lost their lives and another 35 were wounded. The lone gunman drove to a nearby Islamic centre where he shot twelve more victims and was arrested at gunpoint on his way to another mosque.

As Fathers Day approaches, here in Australia, I found this poignant memorial to those fathers who never returned home:

I’ve never visited the Christchurch mosques, but I dare say that they too have that same spiritual quality about them, that pervades all places of worship. The acknowledgement that there is something unseen, something powerful, something beyond our understanding.

The human patina of the deep thoughts and heartfelt peace of worship attaches to these places. Sometimes I sit quietly and meditate, feeling a special atmosphere. Sometimes I turn my gaze upwards. I might not believe in a paradise beyond the clouds, but I can accept that our feelings of higher things and a stronger light come from above.

And sometimes I wander through the graveyards that often accompany such places, reading the names and dates, thinking of those who have passed this way, are passing at the moment, and will come by on the same path in future.

We are all connected, and it is love that connects us. Love and respect. What possible differences can outweigh the bonds of our shared humanity; our childlike wonder at being present in this beautiful present, and our respect for the teachings, the heritage and the culture that have brought us here?

For the fathers

We all have fathers. Those who lost their lives in Christchurch were mostly men of a certain age. Fathers, most of them. Just like the older generations in Zanjan and throughout Iran, parents and grandparents of the youngsters who do their best to find romance through the modest coverings of hijab.

This Fathers’ Day, please pause for a moment to remember the fathers who never returned home in Christchurch, and send up some thoughts that they did not die in vain, that we might think of them, and think of the love of family, of children, of the sweet joy of simply being alive in this marvellous world, which, despite the best efforts of a few, is filled with love.

Britni