h2>Dating : Cue the Violins: Lessons From a Life Well-Lived

Arthur’s second lesson: Strive for, and appreciate, excellence.

I’ve taken many hours to write this post because of all the things I’ve left out: all the details about violins, and great violinists (many of whom Arthur knew and played beside), and music in general and classical music in particular.

I kept a diary during the time I took lessons, but I’d need thousands of words to recount those stories here.

So let me — like music, like poetry — try to compress things.

Imagine it’s before sunrise on Saturday morning. You are home, practicing a violin in a downstairs bathroom with high ceilings and excellent acoustics. Behind a closed door, you aren’t disturbing the rest of your family.

You struggle, but the music doesn’t come.

Violinists can play a simple “C” note a thousand different ways, depending on finger placement and pressure and bow movement. All the ways you play a “C” sound awful.

Then you pack your grandmother’s restored old violin in the new case that you bought (because your teacher said that other musicians will judge you on your case… it’s one of those unwritten rules, reminiscent of when dads explain the secret etiquette of golf). And you drive to a suburban home in a neighboring town and ring the doorbell that is the wake-up call for your violin teacher.

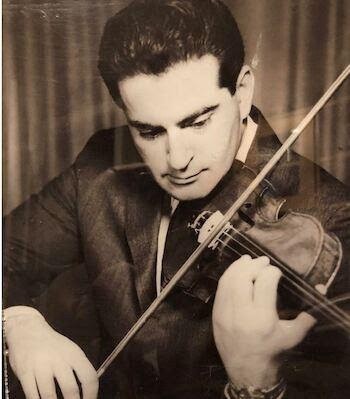

Arthur Samuels, now in his 80s, shuffles to answer the door and leads you to his studio. He smells like sleep. He absently reaches for his violin.

Loud and clear, you hear the “C” you were trying to replicate. It’s followed by note after note after note in quick succession, and each tone is graceful and effortless and evocative.

It’s Arthur, playing a simple warmup exercise. You get goosebumps.

Malcolm Gladwell will tell you that what Arthur just did resulted from a lifetime of experience and at least 10,000 hours of appropriate, guided practice.

I will tell you, it’s magic.

Hard as I tried, I could never replicate that magic. Still, the hours I spent with Arthur taught me to appreciate the violin, and this has been a blessing to me and has extended to other areas of my life.

Midway through my second year of lessons, both Arthur and I realistically concluded that I was a horrible violinist. I am impatient; I have no sense of rhythm and, most damning of all, my middle-aged fingers and wrist movements physically could not produce even an approximation of what Arthur could literally play in his sleep.

But Arthur would tell me stories about the great violinists. Stories about his own career. He played tapes and records for me. What Arthur lacked in computer literacy, he made up for in curiosity, so I taught him how to find and download YouTube videos. I’d project violin performances to his TV and we’d listen and watch them together. He’d critique each one, except for performances by Jascha Heifetz, which were always flawless.

I learned to love the violin.

I remember trying to hold back tears during a recital I dragged my wife to in Teaneck, NJ. A twig-armed young violinist tuned up by playing pitch-perfect phrases from Vivaldi at a very fast speed. Her bow bounced from one non-adjacent string to another with the faintest flutter of her slender forearm, with seemingly as much effort and interest as if she were flicking a butterfly from her shoulder.

My corollary to Arthur’s second lesson: Sometimes, when I am at my very best as a writer, I hear his encouraging voice in my head.

This mitzvah is a constant reminder to be confident and ever-curious as a writer. Many years after he stopped giving me “violin lessons” and to this very day, Arthur still encourages the belief that I can transcend my own mediocrity, even as the limits of my abilities and my accomplishments come more into focus with the passing of time.

Arthur tells me that when I write, I can do anything.

My words can keep pace with the young violinist in Teaneck. They can be just as fancy as her grace notes. I can provide the countermelody and add perspective to her careless perfection.

All this, and I’m just warming up.