h2>Dating : The Color of Everything

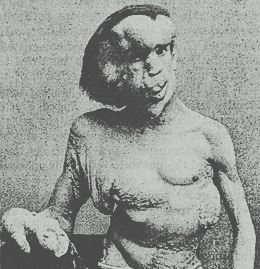

I was a man, brutishly deformed, repulsive, a hard thing to look at…in love. I was fed well enough and I was warm most of the time. I have no recollections of being scolded by a father, assured by a mother. I have never touched a woman, given a name to a son or a daughter. There was that cake, chocolate. I have no regrets.

In those first few moments after my passing, there was nothing to do but watch. I feel my remains were given due respect. I wasn’t offended by the cruelty, the coarseness of that rope and I was glad my hand held to my wrist. I wasn’t sure it would. But it did. And now, I am neither warm nor cold.

Early on my last morning, the wheelbarrow rolled hard. The weight of it stretched and pained the sinew in my arms, my shoulders. Its rubber tire crushed a path through the hoarfrost up the middle of a pasture gone feral. I could feel the black sky begin to blue. Down at the house the light from that woman’s room came on. I considered her. Then there was a light in the hall, then the kitchen.

A cruel wind bit at my cheeks and cut through my canvas coat. I was cold, tired. Venus was low in the sky though bright in the southwest. My bones winced against the strain as I raised my fist heavenward, emptying the wheelbarrow. Piss wet straw, chicken crap, all sorts of barnyard stuff, slid from the wheelbarrow into a mound, there, in the middle of years of other mounds. I was worried for Elizabeth.

The sound of a man breathing hard, a dry axle squeaking, stirred the hens. They churdled, clucked and cooed as I passed the coop. Light from a bare bulb spilled from the barn’s open door into the yard. I could hear the pigs beginning to move, grunting about.

Elizabeth was in the barn. It had been days since she had made any sort of movement of consequence. Her eyes would open now and again, shallow-like and dull. I had no idea how to go about finding a five hundred pound sow’s pulse though I tried. Her breath was faint, all elusive at times.

She had fresh straw. I had been washing her, keeping her pink. I wasn’t sure all this mattered to her. I wasn’t even sure if all this was right or fair to her. It’s not how she had lived. But I did these things anyway.

A bowl of cream milk and my portion of oatmeal from yesterday’s breakfast sat undisturbed, inches from her nose. I knelt beside her. I believed she would be gone soon. I wanted to touch her, to somehow let life flow from me into her. I draped my body over hers. She was yet warm, much warmer than myself. So I held myself around her, using her.

Elizabeth’s eyes sprung open, glossed with fear, anger. She snorted and violently kicked herself up to her hooves. I held on when I should have let loose. For a moment she was able to keep herself standing upright, quivering on all fours, my body lifted with hers. Then she fell and died or died and fell…I don’t know. She collapsed, hind ways first. She rolled, never minding me. Now, pinned beneath her, I couldn’t move, could hardly breathe.

From the floor of the barn beneath Elizabeth’s corpse, I heard the screen door slap on the back porch of that woman’s house. I knew she had set an apple and a bowl of oatmeal on the porch railing, my breakfast. Then the more distant slap of the screen door on the front porch. I heard the rusty door of her truck cry while being opened. I heard it slammed shut. She fired the engine and I listened to it’s warmth as it idled. Then the sound of tires on gravel and I knew she was gone. The wind had died down. There was no more whistling through the barn walls. Except for the hens churdling, pigs grunting, everything was quiet.

In those first few moments, I considered my circumstance more of an embarrassment than such a dire, hopeless sort of thing, being trapped beneath a dead sow and all. Then it occurred to me, my rescue could only come at the hand of someone wandering into this barn. No one ever wandered into this barn. I had no voice to cry out with; a fragment of my deformities.

My hope became that woman. This evening, after she returned from work, she would look to retrieve my empty bowl from the porch rail and replace it with something warm for dinner. The untouched apple and the cold oatmeal would speak to her for me, telling her something was wrong. About nine hours off.

When Ed was alive, he would come out to this barn now and again. Most times, chores would bring him out here. Other times, I suppose it was something between duty and benevolence. He would bring me fresh bedding and supplies; boxes of crackers, tins of sardines, cans of beans, those sorts of things. Every so often, in the musk of a summer evening, he would come out and set a six-pack of beer on the barn floor between himself and me. He would sit back on a bale of hay. I would sit on the strawed floor, leaning against a stall wall. We would drink beer. Ed would talk. I would listen. He would tell me things; things I don’t believe he would or could talk about with anyone else. He knew his confessions were locked inside of me. Deformities wouldn’t allow me to repeat them. Ed was the only one who could begin to hear meaning in the gurgles and grunts that came from my throat. But I was sure that he was sure I could understand him. These conversations made me feel something of a whole man, a friend to a man. These moments were rare but they were enough. Now that I have left that place, I’m going to search Ed out and tell him this.

It was on one of those summer evenings that Ed first spoke of that woman. He was so unsure. He talked very little of love, nothing of desire or passion. Ed reasoned more on such things as shared chores, combined incomes, the convenience of a warm body. Ed was being honest. It saddened him that she was being just as honest.

Last I’ve been told, Elizabeth weighed in at over five hundred pounds. Except for my face, my left arm and shoulder, she covered me completely. My left knee throbbed. It was bent back and inward, left ankle trapped under the back of my right knee, everything held hard to the barn floor by the force of Elizabeth’s body. Below my knees, everything tingled.

Sunlight through knotholes, gaps and cracks was now beaming into the barn, slicing everything. Pigs were all awake. I could hear them moving about, hungry, grumpy. Elizabeth’s hind side lay hard against my right ear. I couldn’t move my head. With my free arm I could reach handfuls of straw and nothing else. Wasn’t much I could see; a five foot arc of matted straw, a portion of a stall wall, upwards, two rafters and the underside of the barn’s tin roof between them. Everything was made golden by the sunrise.

One afternoon, early this past summer, Ed came out to the barn. He didn’t come all the way in. He leaned against the doorway, looked down at the strawed floor for a long moment then said, more so to the floor than to me, “I’ve decided. I’m gonna go fetch her. I’ll be gone a couple of days. I’ll make sure you have everything you need in the meantime.”

I wasn’t happy for Ed. The outcome of this, the happiness, remained to be seen. But I hoped for him. I moved toward the doorway. I reached and touched his arm, nodded my head, telling him I understood. I can’t recall, before or since ever intentionally touching another human being.

The next morning Ed was true to his word. He brought out clean bedding and supplies. He included a box of glazed donuts and a quart of Schlitz beer. I wasn’t scared, maybe a little anxious. Even though on most days I saw very little of him, I was always comfortable knowing he was in the house, the fields, somewhere nearby. Ed left.

It was two days later, late afternoon, more nearly early evening when Ed returned. The shadows of trees were stretching across the fields, cooling the air, changing the colors of everything, the last chord of the sun beginning its surrender to the night, when I first made sight of that woman.

I had been up on the knoll out past the upper pasture digging for bait worms. I was a good ways from the house and didn’t hear Ed’s truck pull in. The three of us, Ed, that woman, me, we were all caught, taken aback.

Ed and that woman were in the yard between the house and the barn. Ed was showing his bride the lay of her new home. Seemed as though there were miles between them as they stood facing one another. Her hands were thrust wrist deep into the front pockets of her jeans. Her shoulders scrunched forward towards Ed as he gestured with his hands, showing her the extent of all that was his, now theirs. Their smiles were weak, careful.

The path from the knoll back to the barn covered some distance. Walking it required a great deal of me. I was a man whose very bones were wrongly fitted. Every step demanded will and attention. Because of this, I didn’t become aware of her until it was too late. It was a warm day. I thought I was alone. I wasn’t all that well covered, shirtless. Then, there was no place to hide, no way to temper what she was seeing. I’m sure Ed had made every effort to prepare his bride for the sight of me, a man whose flesh dripped from a skeleton, beat and bent. She wasn’t all that prepared.

When I was alive, there had never been anything inside of me that could threaten or do harm to another. Though, the whole of my life, fear had always been the response that introduced me. The fear would pass and be replaced by revulsion. After the revulsion settled a bit, others would define themselves by what came next. That woman, her hands came out of her pockets and she reached around Ed, clinging. Her face pressed into his chest, her eyes closed hard. Ed’s eyes were worried. It wasn’t her fault. I should have been more covered. That night was the first night I dreamed of her.

It had been several hours since Elizabeth had died on me. The warmth of her body was evaporating, turning toward a clamminess. I was becoming cold. Not the sort of cold you feel on your skin, but a cold that radiates from the heart, the lungs. The cold, the numbness, in a way presented a gift; I had never felt so little pain. I could hear agitation in the snortings of the pigs, anger in the calls of the roosters. They had missed a meal. My thoughts were becoming aimless, wandering things. Much like the thoughts a man thinks at night in those moments before he falls asleep, not quite yet dreaming. I imagined, saw myself, whole, standing upright, board straight.

As months went by, Ed, that woman, myself, we all evolved into something new, an entity, a sum of souls and land, each bringing our own to the whole of who and what we were; a potluck of sorts.

It took some time, some learning. Ed was offered a good job in town at the farm implement supplier. His qualifications were a hands-on understanding of tractor hydraulics and a fluency in the language of farmers. That woman was strong. She could endure the heat and dust, the hours in the field on a tractor. In the evenings, after my dinner, I would pull the tractor out of the barn; fueled and hitched with whatever machinery she needed the next morning; the tiller, the reaper, the baler, whatever was called for. She wasn’t all that strong. We all discovered how difficult it is to farm when you won’t go near the barn. Ed quit his job at the implement supplier. That woman took a job in town at the Wal-Mart. Ed hitched his own tractor, one less thing for me to do. I missed doing it.

No one ever asked me to hide. And I never thought of it as such a sad thing as hiding. To me, a courtesy, a civility, I think. Before that woman, Ed wasn’t one to have many visitors. The back of the house stood flat between the barn and the front drive and a good bit of the gravel road that led to the house. So, most generally, I wouldn’t be able to see visitors arrive. Gravel speaks, porch floors creak and doors squeak, I most always knew when they were there. No one ever asked me to find things to busy myself with in the barn at these times. It was just the proper thing to do.

One Sunday, Ed’s last, he went into town early. Came back early. He spent about three-quarters of an hour in the back yard assembling a new propane grill. Every time that woman came out of the house, back in again, there was a whine of springs and a breath of air, a slap as the screened door shuddered. She stretched a checkered, plastic tablecloth over the picnic table. She chewed off strips of duct tape and secured the hanging ends of the tablecloth to the underside of the picnic table to brace it against the breeze. In and out of the house, mustard, ketchup, a bowl of baked beans, a potato salad she had been working on since early that morning. I didn’t see when these people arrived. I just knew they were there.

In the barn wall, at the foot of my bunk, there was a small knothole, eye level if I sat on the edge of my bunk. Through that little hole, I joined a picnic.

Those kids were doing most of the talking. That man and that other woman were mostly telling those kids to shush or behave. Ed was smiling a lot. He had an infant on his knee, bouncing it nervously, near to death I think. Didn’t say a whole lot, Ed I mean. That woman must have offered her guest more of her potato salad near five times. They grilled burgers and made pitchers of Margarita. Then they played croquette.

I suppose that little girl was near nine or ten years old, I think. Two little brothers, one about seven or eight, the other, the infant nearly killed on Ed’s knee. The croquette was becoming serious, margaritas…many. The game was close. I was pulling for Ed and that woman. Almost felt part of that game. No one noticed that girl wander off toward the back of the barn.

She must have tipped-toed. I didn’t hear her. I just turned. For some reason I just turned and she was there. Her name was Helen. I know this because she stood in the doorway of my home and said to me, “My name is Helen.”

I nodded. I tried to say, “Hello Helen.” without breathing, without exhaling. I nodded. Helen glanced around. I wasn’t ashamed because my bunk was made tight and my stores were neatly stacked.

“Do you live here?”

I nodded.

“There’s more burgers out there. I won’t vouch for that potato salad.” She walked a small circle, made note of the whole of my home. “You should come out and get some before it all gets too cold.” I nodded. Helen pranced out. I don’t know who won the croquette game.

Next day, Ed was dead. We didn’t know it until well past dinner. That woman came out of the house. She walked across the yard to the front side of the barn. She called through the wall. “Excuse me! Ed’s been out an awful long time. I think we…you should go check on him. I can’t hear no tractor.” Then she went back into the house.

The shadows of trees were stretching across the fields, cooling the air, changing the colors of everything, the last chord of the sun beginning its surrender to the night, when I found Ed. I could see in his face that he had fought it hard. His shoulders, the back of his head sunk deep into the soft, tilled earth of that hillside. The backs of his arms, his elbows, even deeper, pushed into the ground by his efforts. His hands were puffed and white, stiff against the tipped tractor, as if they were yet busy trying to lift this impossible weight off his chest. A single fly explored the corner of his mouth. I brushed it aside. I found his hat. I set it low on his brow in respect of his eyes.

I didn’t know how to tell that woman. I had no way to tell that woman. Night was at the threshold. The moon, large and frowning was rising beyond the knoll. I had never been this close to that woman. She stood on the back porch, her hands fixed hard on the railing. I was hooded. Mostly my back kept to her, but a glimpse, just a glimpse. She asked one thing. I shook my head. She asked another thing. I shook my head. There was a wind in her voice when she asked the last thing. I nodded. She swayed; a whispered moan. I went back to the barn.

By now it was mid-afternoon, still several hours before that woman was due home. I knew it was becoming gray outside. There were no more arrows of light piercing the barns walls. The wind was picking up. The barn was beginning to breathe, to wheeze. Cold radiating from deep inside. I was still mostly conscious. I felt bad for Elizabeth. I hoped that woman wouldn’t be too angry with me for allowing her hog to die.

The rest of that summer, living became awkward. That woman hired a man to bale the hay. The late corn Ed planted took root, grew, was never harvested, rotted in the field. By mid-winter, I was scraping the bottom of the crib to feed the hogs. The four cows in the bottom pasture fared well enough for a while. Then that woman slaughtered and lockered one, sold the other three. Two of the pigs got slaughtered, two sold, she kept the other twelve. Those pigs and the hens were now my main occupation.

I would leave eggs on the back porch. The hens, when their numbers exceeded the coop, I would kill, pluck and render a couple, leave them on the porch in a cooler. When feed got low I would fold the empty bags, leave them on the back porch. In a day or two I would find full ones leaned against the side of the house. It was our way of doing things.

As the days passed by, that woman and me, we learned, we found a footing. Every morning, the slap of the screen door would tell me when it was time for breakfast. I would give her a moment to disappear back into the house before I would head out to the porch rail to fetch my meals.

Now, God forgive me, I truly believe Ed was one of the most kind, most beautiful human beings to have ever graced the face of this earth…and I have never once thought small of him…Ed was a good man; a very good man. But that woman…she could cook.

There were times, the things I found on that porch rail…well, I just didn’t know such things existed. Did you know…they make this food called Wheaties? They’re sort of like flakes of sweet bread crust only different. They come in little box that you cut open with a knife, fold the cardboard back and then pour cream milk right into that little box and dig it out with a spoon.

Not every day, but most days, for years, when Ed was here, I ate the same things; oatmeal and an apple for breakfast…beans and rice for dinner. Every now and again, bacon and eggs, fried chicken once in a while, but for the most part it was beans and rice and the tins of sardines, the crackers and such that Ed made sure I had in the barn. Since that woman, I have tasted peanut butter and jelly, banana, hot dogs with sauerkraut piled on top…something of a shock the first time, but I got right used to the sauerkraut quick enough…I never knew what that woman was going to set out. I never knew the world was so big.

Sometimes, under a breakfast bowl, I’d find a handwritten note very politely pointing out additional chores that might need done that day. And if that woman felt the extra chores were an exceptional burden for me…alongside my breakfast…glazed donuts.

Ed once told me that a woman knows, deep in her very nature, how to work a man. I think Ed was right. I loved glazed donuts. At the time of my passing, I still had every one of those notes saved beneath my bunk. Likely, my most prized possessions. It was those notes that made me want to be…just a little more than I was.

Ed, he kept a pen tied to a clipboard and hanging on a nail out here in the barn. It’s how he kept track of things around the farm. The mangled mess that was my tongue and throat wasn’t suited for shaping words. I could read fair enough but years ago I had given up trying to write. The twistedness of my hands made holding small things like pens difficult. I wanted…I needed to try again.

Took about two days; forming letters was hard and hurt my hands. But I did it. I practiced and practiced making those marks…just two words. About two days after that, that woman came out set out my breakfast on the rail. She set a note under my cup; something about lighting the burn barrel that day. A couple of glazed donuts were wrapped up beside it. Like any other day, I ate my breakfast, did my chores, at the end of the day, just before she was due to return from the Walmart, I set my cleaned bowl and cup back on the rail for her to fetch. I folded the note I had made and set it under the cup. It said… Thank you.

Couldn’t really feel the weight of Elizabeth’s body no more. Felt more like a blanket, a cocoon. Finding room for air in my lungs was the hard thing; the thing I had to work at. By now, I had a pretty good idea how this was going to end. Something about the numbness, the quiet in my body, just didn’t feel bad. Just didn’t feel the end would be such a horrible sort of thing.

I thought about vultures, how they lived in the sky, coming to earth only to eat, to sleep. There were times I’d spend long moments up atop the knoll, nearly fallen into a trance, watching them soar; sometimes for so long my neck kinked, just waiting for one, out of necessity, to flap its wings. Now, notwithstanding the unfortunate act of sticking your head up a four day dead coyote’s butt for breakfast…you have no natural enemies. Even those with rifles won’t waste a bullet because they resent the very idea of your carcass. You’re anathema, untouchable…and so free…and you live in the sky.

One Sunday morning, near the middle of July, I was sweeping up in the barn. Out of the corner of my eye, a movement in the doorway caught my attention. It was a cat; gray with patches of white, a bit on the smallish side, I think. From a distance, it didn’t look none too healthy. It was shaping up to be a very warm day but the cat seemed to be shivering from cold. It didn’t come all the way into the barn but just sort of stood in the doorway, not really looking at anything, no curiosity about it. Just stood there shivering.

I let my broom lean against a stall and stepped over to the doorway. Even though I was standing right over it, the cat didn’t seem to notice me. That’s when I noticed the long, deep gash running from its rump then disappearing under its belly. It wasn’t shivering from cold but trembling from infection and weakness. The cat lay, or sort of collapsed, onto its side, right there in the doorway. And that’s when I saw the gash was so deep that I could see all the way to its guts and the swarm of maggots shimmering and squirming inside.

The sight scared me at first and made me step back, gasping. Took me a moment to gather myself but I moved near and squatted next to the creature for a closer look. Several times, I had to turn away to keep myself from throwing up. It was a hard thing seeing this.

For the life of me, i can’t tell you how I felt. I just couldn’t think of what I could possibly do to help this little guy; seemed so hopeless. I felt so helpless. The wound was so deep.

I stood up and hurried to my bunk, reached underneath, pulled out a cardboard boot box. I dumped the contents, all those notes that woman leaves me on the rail, onto my bunk. I found some rags and lined the bottom. It was a hard thing for me to bring myself to do, almost made me sick to my stomach, but I slid my hands neath the cat and lifted the little guy into the shoe box and brought him into my quarters and set him on my bunk. I just didn’t know what else to do. I paced and thought hard. Didn’t know if what I intended to do next was the right thing, but it was all I could come up with.

I unfolded my spare blanket and tossed it over my head leaving a narrow slit allowing me to see where I was going. I carried the cat in the box outside. I set him on the porch. I rapped on the door; a thing I had never before even thought of doing. I hurried down the steps and stood in the yard; made sure my blanket had me good and covered. That woman opened the door a crack and peered out. She spoke to me.

“What is it? Is something wrong?”

I extended my arm and pointed to the porch floor. That woman looked down. It wasn’t a scream. It wasn’t a cry or a gasp. It was the sound of the human spirit falling; sort of a whimper. The door slammed shut. I heard that whimper again from behind the closed door.

I felt shame. I had done the wrong thing. I shouldn’t have involved her. I shouldn’t have let her see this. I just stood there. For the first time in my life, I felt abandoned. Then the door opened again. That woman came out.

She said, “Look at me.”

I turned and peered through the slit in my blanket. She was so beautiful.

She held up a brown bottle. “This is peroxide. You need to pour this directly into the wound.”

I nodded.

She held up a small paint brush. “You need to dip this into the peroxide and gently sweep out all those maggots.”

I nodded. The thought of doing so made me shake.

That woman held up a roll of gauze. “You then need to close the wound best you can to keep it clean. Not too tight, now.

I nodded.

She was pale. “Do the best you can with it today and bring it back out to the porch tomorrow when I get home from work. We’ll take another look and see how it’s doing.”

It was quiet for a moment. I heard her sigh. “It doesn’t look very good. We’ll give it our best shot.”

I nodded.

Another quiet moment, another sigh, she went inside. She gently closed the screen door behind her. I picked up the cat.

I wasn’t much surprised at how the cats’ body winced when I poured the peroxide into the wound. I was surprised by its tense calm at the feel of that brush’s soft bristles sweeping deep inside its body. This was a hard thing for me to do. I got it all, I think. I wrapped the cat in gauze and sat with it through the night, putting drops of milk on my fingers in hopes it would lick some into itself.

Come morning, cat was still with me. I fed the pigs, the chickens, tidied up the coop; looked in on the cat. Its eyes were open. Didn’t seem to be looking at nothing. His eyes seemed unnaturally clear, I think.

Sun was up. A ray of warm light fell from the window. I slid the cat in the box into the light. His eyes closed at the warmth. Poured some milk in a jar lid; set it next to his nose. Appeared to be day-dreaming. I went back to my chores.

Later, I was watching it breathe, its’ chest rising, falling, when I heard the sound of truck tires on gravel. In less than a minute, I was standing in the yard; covered by my blanket, cat in the box was on the porch. I had already knocked.

I didn’t turn to look at her this time cause she didn’t tell me to. I heard her knees pop when she knelt over the cat. They popped again when she stood.

“You did a good job.”

I nodded

“I’m gonna fetch some more supplies. I’ll be right back.”

I nodded.

She let the screen door slap. Didn’t close the big door behind her. Could hear her rummaging, screen door slapping again. I heard her setting things on the porch rail.

“I’m sorry. You have to do it all again. I know it’s hard. Still don’t look all that good but I think you might have given the poor thing a fighting chance.

I heard her pat her hands on her jeans.

“Dinner will be ready in about an hour and half or so. You might want to get it done with before then.”

It was quiet for a moment before I heard the screen door slap. I let it be quiet for a moment more before I gathered up the supplies and the cat in the box. That woman, she left a little can of Friskies with a pull top on the rail. It was hard to remove the smelly dressing and put the cat and myself through it all again, but I did. A beans and rice night. Didn’t have much of an appetite.

Next morning, as I woke in the blackness of the pre-dawn, I let my hand slip down beside my bunk and felt around. My fingers found the cat in the box beside my bunk. Cat was cold, hard. I didn’t cry. I just closed my eyes and fell asleep again. I dreamed of Ed. He was smiling. We spoke for a time. He told me all was well. Then it was time to tend to the pigs and the chickens.

Wasn’t in no hurry when I dumped cobs and meal into the pigs’ trough or when I scattered scratch for the chickens. Next chore was going to be the hard thing, putting my courageous little buddy to rest. Hadn’t given him no name. I wished I had.

I could have just tucked the cat in the box under my one arm and carried my shovel in the other. Something just seemed right about laying the little guy in the wheelbarrow and letting him ride through the pasture up to the knoll.

Digging was a hard thing for me. When I was hunting bait worms, not so bad. Just a matter of stamping the spade into the dirt, leaning on the handle and turning over a pile of sod. Never really needed to accomplish anything resembling an actual hole. This was hard. The box the cat was laid in was, to me, sort of a special box. I felt small for wishing inside I had found one not so large. I tried to think of my chore as simply looking deeper for bait worms. I’d stamp the spade into the dirt, lean on the handle, let the shovel fall to the side as I dropped to my knees and pulled scoops of loosed dirt out of the hole with my hands. I intended to keep doing this til I had a hole of sufficient size. Just hadn’t the strength to be lifting and tossing shovels full of dirt. I leaned against the oak tree and rested between shovels full. Figured this was going to take some time.

I didn’t see her coming through the pasture and then making her way up the knoll. Didn’t even hear her when she was near, right behind me. Fact is, I don’t know how long she was there before I felt her touch my shoulder and then she bent down and took the shovel into her hands. I scooted hurried like on my knees a quarter-way around the oak. I was shocked but found the presence of mind to realize the back, right side of my head was toward her, the more grotesque side. I spun on my knees so the back, left side was more toward her. I kept my sight downward and watched her dig out of the corner of my eye.

She accomplished a good hole right quick. Stood there for a moment, said quietly, “You did well by the little guy. I’ll leave you with him. I’ll go ahead and haul the wheelbarrow back to the barn. I’m sorry.”

Sky was peppered with vultures, silhouetted in the brilliance of the sun. I apologized to them for denying them the cat as I covered him good. I leaned against the oak, spoke with Ed a bit.

Breath was failing me. Not as large a thing as one might suppose, I suppose. Peace means a lot. I wasn’t so much tired as I was just simply done. Just done; a relief of sorts. I could hear a helpless panic in the snortings of the pigs. I felt bad for them but I knew they’d be fine soon enough. That woman would tend to them in due time.

Strange thing about passing, a whole life is discovered in the things left behind. An urge, a wanting the size of the sky, to be able to walk back to my quarters just one more time and make sure my bunk was made tight as it could be, my spare blanket folded, my stores stacked good, my coat hung on the rack. It was all those handwritten notes that I thought about the most. She would find them; bundled, tied with a string neath my bunk. She would realize the things one might deem as having served their usefulness and is now, to them, rubbish…another cherishes. It’s the small things.

Near the end of the summer that Ed died, I had the greatest day of my life. It was a strange thing. I so wished Ed was here to see it. He would have been proud. But if he would have been here, it would have been his day, not mine.

It was late on a dry, breezy, Saturday afternoon. That woman was in the backyard taking sheets off the line, her hair, like the sheets, being lifted in the wind. I was in the barn, standing back in the dim light, watching through the opened man door.

A truck had driven past the house. It stopped a short ways down the road. There was a whole lot of whooping and hollering coming from the boys, the young men, piled in it. The trucked backed up, pulled into the drive.

Four young men came around the side of the house and found her. Each had a bottle of beer in their hand. They politely stood in a line in front of her. They all grinned, one spoke. At first, that woman smiled helpfully, pointing further down the road, like she was giving them directions. Then her smile melted when the young men’s grins became more like sneers. They shuffled themselves around her, boxing her in. Once again, like the very first time I saw her, there was fear in her eyes.

I watched from the barn, weak, helpless. My body shook, tears in my eyes, tears in hers. I don’t really have any recollection of the next moments, of my next movements. Just, there I was, a morbid silhouette, framed in the brilliance of the late day sun. My feet apart in a wide, sturdy stance, hands in the air, spread wide, making fist around the long handle of a hoe, pumping it toward the sky, my lungs filling with air then emptying with a hard hiss, filling again, hissing again, eyes, crazy wide, ugly as sin. They didn’t attack. They didn’t run. They walked away, looking back over their shoulders.

That woman ran into the house, called the sheriff. I went back into the barn. An hour later, I was sitting on the edge of my bunk. Sheriff walked in, stood in my doorway, looked long at me. He nodded his head. He left. Next morning, on the porch rail, fried eggs, bacon, fried potatoes, a homemade chocolate cake…the whole cake.

Summer became fall, cooling the air, changing the colors of everything. It rained some; mornings sometimes frosted, afternoons yet warm enough, evenings just right for sleeping. I always liked the sound of rain on the barn’s tin roof. Felt a kinship with thunder. I was amazed…fearfully hypnotized…by lightning. There’d be deer, nearing rut, watching me from the tree lines, when in the morning’s blue-blackness I made my way up the pasture with my wheelbarrow. It gets colder. Then geese and panicked dove, leaves made golden and skies now grey, a need for a jacket, sometimes a coat, then an extra blanket, time to fire up the wood stove in the barn. Fall was always good to me.

I could hear the shotguns popping on the neighboring farms, dropping dove, quail or pheasant. Ed never cared much for hunting. Said he lost his taste for such things in a place called Nam. Though, now and again, he’d let ‘em walk the fence lines and windbreaks with their dogs. Seemed a lot of work to me when all I needed to do was step into the coop and wring a chicken’s neck. At the end of the day, near sunset, when the hunters were loading their guns and prey into their cars, they’d often leave some birds with Ed. Ed would leave em with me to clean and dress. I liked dove; quail even better. But every bite of pheasant was a wonder, tangy and wild. Nothing like chicken.

I think that woman was leery of strangers but she’d still sometimes let em hunt if they asked right enough. Others she’d send down the road. Sometimes she wouldn’t even answer the door. I often wondered if she was so particular of strangers before that one day this past summer.

Late one morning, near the end of November, I could smell something cooking in her kitchen, for hours, even all the way into the barn. I was sitting on the edge of my bunk, my tummy bubbling in tune with what my nose was smelling. Heard the screen door slap. Then I heard her call from outside, through the barn wall. “I have some chores I’d like you to help me with!” This was an oddity. Then I heard, “Come on out to the porch when you can!” I was a little scared.

Didn’t put no blanket over my head. I was dressed for late fall and covered well enough I figured. I put on my canvas hat. It had a canvas apron around the back and sides that hung to my shoulders and could be tied closed over my cheeks, intended to keep chilly winds from biting my neck and shoulders when I needed to do chores in bad weather. Best I could do.

I stood at the foot of the stairs. I saw a folded up table and two folded up chairs leaning against the rail. Ed would carry these things out to the barn now and again and we’d sit at the table and play rummy and drink beer. Not often, though enough. The screen door was shut but the big wooden door was wide open. I could vaguely see her through the screen, busy in the kitchen. She didn’t look up from her chores when she called, “Carry that table and chairs out to the barn.” I nodded. Don’t know if she saw me do this. Then she said, “Sweep a place clean like and set em up.” I nodded. A bit bewildered. Then she said, without quitting her work “Make sure that stove is good and stoked.” I nodded. “There’ll be more out here on the porch that needs to be hauled out to the barn so don’t dally much.” I nodded.

Ed would have put both chairs under one arm and carried the table with other and still manage a six pack of beer and a deck of cards all in one trip. Took me three. I swept out a big spot on the floor. Stoked the fire real good. Didn’t know what I should do next, wait here for that woman to call or go stand at the porch and wait there. Heard the screen door slap again. She said not to dally so I went outside.

On the steps there were plates, forks and knives, a glass butter dish, a glass plate of sweet rolls covered in clear plastic, a glass bowl with a glass lid, full of reddish, purplish stuff, a glass pan with a glass cover full of what looked sort of like mushy bread with nuts and raisins kneaded through it. I was careful with all that glass; made several trips. Got it all to the barn, set everything on the table cause I couldn’t reckon what else I was supposed to do with it all. Stood there for a moment, wondering what I should do next.

Heard the screen door slap. Two drinking glasses, a glass pitcher of cream milk, a glass plate full of corn still on the cob, covered in plastic; made several more trips and was real careful cause of all that glass. Didn’t drop nothing. Came out and stood at the stairs for a moment.

Through the screen door, “Wash up best you can then take a seat. Be out in a moment.”

I ain’t one to swear much, bang my head or smash a finger, times like that, but truly, my one thought was…”Oh shit!”

I was just sitting there in a chair, wondering of all this stuff on the table, when she came in. Oven mitts on her hands up to her elbows, she carried a big roasting pan. Didn’t know what was in that pan. It was covered in foil. Smelled so good thought I might faint. Had a huge knife in her teeth. I turned in my chair a bit, letting my back be to her a bit. I was scared. She set the big pan on the table. I don’t think she was none too satisfied with the way I had set everything else on the table ‘cause she spent some time rearranging things. Did look right nice.

“We’re going to have thanksgiving together. Seems only right. Don’t you think?” Din’t know quite what to think but I nodded.

That woman set an ear of corn on her plate…then one on mine. She uncovered the mushy bread looking stuff and dug in with a scoop. Plopped some on her plate…some on mine.

She asked, “Ever had stuffin?” I shook my head.

She took the foil off the roasting pan and I saw the biggest chicken I’d ever seen in my life. “Ever had turkey?” I shook my head; eyes wide at the sight.

The reddish, purplish stuff; learned this was cranberries. Oh my God! You sort of scoop some on your fork with every bite of everything else. And stuffin’…Oh my God! I reckon, left to my own devices, I could eat a pan of it. Oh my God! Turkey…it ain’t chicken. Turkey gravy on stuffin’ with cranberry, it’s what God eats, I reckon. Every time my plate got near empty…she’d fill it with more. I was so happy I coulda cried. Don’t know that I didn’t.

We both sat there quietly for a moment, tummies so full, seemed almost sinful. That woman asked me to excuse her. Said she’d be right back. I heard the screen door slap on the back of the house, a moment more, slapped again. She came back and carved some turkey into a plastic tub and snapped a plastic lid on it. Another, smaller tub of cranberry. Dumped all the stuffin in another and poured some gravy on it before she snapped that lid shut. Slid these tubs across the table and told me I should keep these tubs out here for later. Oh my God!

She got up and took hold of the platter and what was left of the turkey. Said she’d be right back. Heard the screen door slap. Heard it slap again. She gathered up the rest of the corn, the cranberry, said she’d be right back. Heard the screen door slap…heard it slap again. She sat down at the table and slid a box toward me. “Happy Thanksgiving.” Said it was a Walkman. She told me to put a bug like thing in my ear and to roll this little switch. I have since learned I like country music. Couldn’t do it out loud but I learned to sing in my head.

“I did all the cooking. You wash up all these plates in your sink and bring em out to the porch after a while. No hurry. Reckon you might need a nap soon after such a meal.” Sat there quiet like for a moment, said, “Happy Thanksgiving”, one more time. That woman left.

Don’t know how long I sat there. Explored the dials and buttons on the Walkman. Think I cried a bit.

The wind was picking up. A storm gathering. Rain began tapping on the barn’s tin roof. It was nearing the time for that woman to return. Breathing was the most difficult thing. A breath, a heartbeat, a breath, such a burden. So I died that afternoon.

About an hour after my demise, that woman came home. About an hour after that, when she was setting out my dinner, she found my breakfast still on the rail. About an hour after that, when she checked for my cleaned dinner plate, she found my dinner was also untouched. About an hour after that, she came out, walked across the yard to the front of the barn, called through the barn wall. A few minutes later, full of caution I think, stepped into the barn. Didn’t need to get too far in before she saw enough. She called the sheriff.

The sheriff was a slight man. Elizabeth was a monumental mass. I was a wet sack. He made an attempt to roll Elizabeth off of me. Then, he called for help.

The sheriff and those two other men walked circles around me and Elizabeth, scratching their chins. They settled on a course. The two men shoved two-by-fours as far as they could under Elizabeth and pried upward on her. The sheriff hitched one end of a rope to the tractor, the other end tied off to my free hand. Men lifting, tractor tugging at the same time. I wasn’t offended by the cruelty, the coarseness of the rope and I was glad my hand held to my wrist.

That woman stayed in the house. A good thing. I did not wish her to see all this. Not a pretty sight. Not how I wanted to be remembered. Ed’s here somewhere. Think I’ll go find him.