h2>Dating : America Deferred: Love & Life in Lahore

When we moved back to Lahore, I had just finished my kindergarten in Istanbul in a school that was run by the local mosque, just a few blocks away from our family’s apartment. I have but vague memories of the time spent in Istanbul, and most of them have been revived by my rummaging through the diaries that Ammi had stacked in one of the drawers of the dresser in her room that she kept locked at all times, except on occasions when Abu returned back from his myriad business trips in all nooks and corners of the world. In one of the pictures from one of the diaries, I can be seen reciting a song, holding a chiseled green strip of paper in my hands, standing in front of a small makeshift podium at one corner of the classroom. Other children sit cross-legged in a large circular Persian rug in the middle of the room, looking at me intently. The room itself is decorated with origami flowers made from colorful strips of paper, Turkish flags, and cut-out letters of Turkish alphabet. The teacher, clothed in a long blue gown and matching facial covering, stands at the door in the back of the room.

Her name was Fatma Dogan, but we regarded her as Öğretmen Fatma. She was a character that I was both simultaneously fond and scared of. As polite and soft-spoken as she may have been, she exuded an aura of confidence and authority within the four walls of our classroom that intimidated me. She demanded absolute conformity and obedience to her rules, and as such, prior to going about our other daily activities, we always began our days by singing İstiklâl Marşı, the Turkish national anthem, which I unconsciously sing and hum every now and then even nowadays. She was much like Ammi in some ways. They both had hazel blue eyes — although Fatma’s were much lighter than Ammi’s — and were taller and slenderer than most women their age. Ammi and Fatma both wore long dark gowns and burkas, and all parts of their bodies were always veiled, except for their hands and eyes. Fatma also had two children and was fast in her movements and gait like Ammi. However, there the resemblance ended. There was some kind of subtle beauty to Fatma’s eyes and complexion that Ammi’s lacked. Fatma was several shades fairer in complexion than Ammi, and she never wore any make-up in her eyes while Ammi was fond of applying eye shadows and kohl around her eyes and wearing high heels, which I noticed Fatma never did.

Ammi and Fatma had forged an intimate friendship by the time we left for Pakistan. Ammi was one of the few parents who always came to pick their children at the school, which is where Ammi and Fatma had first crossed paths when Ammi came to pick me up from school on the first day of kindergarten. However, just within the course of two or so months, Ammi and Fatma had taken to being close friends, and Ammi would sometimes spend even more than an hour talking with Fatma in our classroom after all the children were sent away with their parents. Ammi didn’t speak Turkish, so their conversations were always in English, a language that I had yet to learn and master. However, from the way they talked, I could make out that whatever they talked about must have been some serious matter, for Ammi, who has quite a knack of laughing, never so much as once let out a laugh in any of their conversations.

Regardless of what they talked about, their friendship had completely lost its mooring once Ammi divulged to her that Abu had now decided to retire from his position as the Counsellor in the Embassy of Pakistan in Turkey, and within just a few days, the flight tickets were booked, suitcases packed, apartment emptied, and we set out for Lahore on a helicopter that was chartered to fly just the three of us to Pakistan. That was my first time flying on an aircraft, or rather the first memory of such an event that abides in my memory, for I was born in Lahore and was shuttled to Istanbul with Ammi and Abu just five days after my birth.

When we landed at the airport in Lahore, a throng of people was awaiting our arrival. At once, I was instantly swallowed by hugs and kisses by people that I was seeing for the first time in my life. As we drove through the streets from the airport to “home,” as Ammi said, the scenes that we came across caught me off guard. There were demonstrations happening all over the streets. It was 1993. Benazir Bhutto, the first female Prime Minister of Pakistan, had won her re-election and come to power anew. Many carried banners that bore warped, maligned images of Bhutto. The crowds were densely packed, shouting, blocking the streets, and moving in a procession toward the direction of Minto Park. People in the houses and the crumbled dwellings flanking the streets were perched on their rooftops and balconies, sometimes chanting along with the protesters who vilified and hurled slurs at Bhutto in the public. There were also men who were dressed in uniforms like those worn by the police; they shielded the protesters from every direction, following the throng as it menacingly filed past street after street, stirring great hullaballoo.

I was immediately enrolled in a school within two weeks of our landing in Lahore. Apu’s youngest sister, Noor, had already made all the arrangements for me to enroll in the first standard at Meridian International School, which was run by a group of Turkish missionaries and touted as the most expensive primary school in all of Lahore. Life, however, was different in Lahore. It seemed much simpler but fuller in so many ways. The heat was more tolerable in the summer, and summer brought a lot of rain showers, which I quickly began being fond of. Our family owned a two-storied house with a backyard and a front lawn, where a cornucopia of flowers, including my favorite flowers, roses and hibiscuses, bloomed perennially. We even owned two cars and two chauffeurs, one for Abu and one for everyone else in the family. Besides Ammi and Abu, Noor and Daadi and Naana also lived in our household, and the six of us ate dinner together every day at 8:00 p.m. until Noor was married off to one of Daadi’s friends’ son and left for Islamabad, leaving Daadi and Naana irreconcilably depressed.

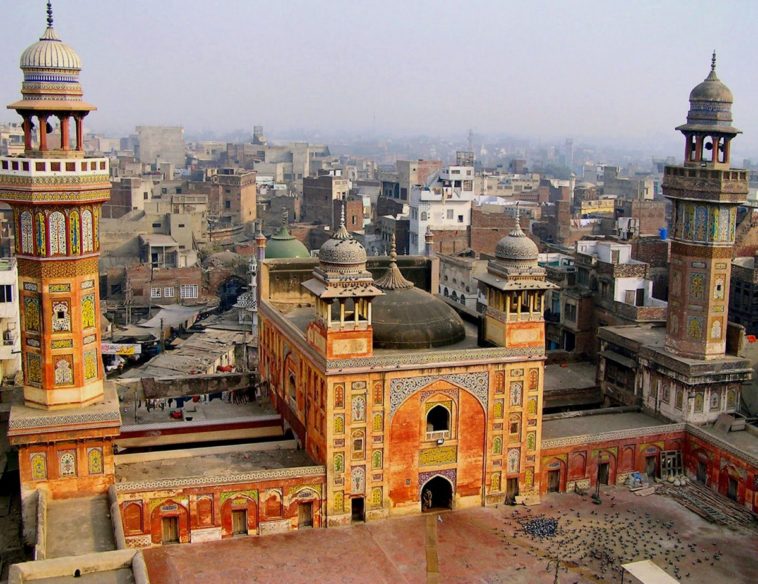

Unlike Ammi and Abu, Daadi and Naana were staunch Muslims, who prayed five times every day. They were always up before dawn, and after taking a shower and before putting so much as a drop of water in their mouths, they began praying after purging any extraneous thoughts from their minds, facing the direction of Mecca, prostrating in one corner of the foyer in our home that was strictly reserved for daily prayers. Daadi and Naana also enrolled me into three-hour-long Quran classes on Wednesday and Sunday evenings in Badsahi Masjid on the outskirts of the Walled City of Lahore, where I learned to read Arabic and recite verses of the Quran. One of our chauffeurs would have escorted me to and from my classes, but Naana always took it upon himself to come with me to all of my classes at the mosque. Most children who came to learn Arabic and read the Quran were escorted by their grandparents, and grandparents often bid their time yammering about their old days in one of the communal praying rooms in the mosque while the children partook in Quran-reading classes.

At Meridian, I quickly became friends with Imran. In fact, I had taken a liking to him as soon as I had first seen him at the school. He had a long, chiseled face with a pointy, prominent nose and sharp jawlines. His eyes were dark and deep and captivating like wells, into which I instantly fell at the first sight of them. Both of our families were sojourners. His father also worked in the Embassy of Pakistan like mine, and his family had returned to Pakistan from the United States after spending a couple of years there after People’s Party rose to power and Bhutto reclaimed the prime-ministership of Pakistan. Imran spoke with a mesermezing American accent, even though he was just my age and hadn’t fully mastered the language. Our parents knew each other, and my parents allowed Imran into our home. He often accompanied our family dinners, and I went to his home on Sundays for dinner with his family. Our parents broke fasts together during the month of Ramadan, convening every evening after sun went down for elaborate meals and gossips. Eid was always celebrated in Imran’s home, where Imran’s mother Mumtaz threw a grand feast, which drew more than a hundred people — distant and close uncles and aunties — from every mohalla of West Lahore. Ammi had started sending some of our maids to Imran’s home to help with the cooking for Eid celebrations, but after a couple of years, Mumtaz’s Lahore-renowned party drew more than two hundred people, and the Khans resorted to ordering their foods from a catering company instead of cooking themselves.

Imran and I spoke candidly about each other’s lives, sharing secrets about our families that we only kept between ourselves. Imran told me about his Abu, Abbas, who had started secretly seeing another woman. Mumtaz had started receiving calls from a woman by the name of Huma Habib, who told everything about Abbas’ whereabouts every day and claimed that Abbas rented a room in a hotel in Huma’s name where they both met and made love to each other in private, averting public’s gaze and the scrutiny of neighbors and relatives. Meanwhile, I confided to Imran about my own Ammi’s erratic behaviors. Ammi had started listening to Qawwali and attending concerts of Rahat Fateh Ali Khan and Runa Laila with her girlfriends, disappearing on certain days until late at night without letting any of us in the family know about her whereabouts. She had always hated going to Ghazal and Qawwali night-outs with Abu when we were in Turkey, and it didn’t quite sit right with me that she had started liking these activities abruptly those days. She had also ceased to wear any of the traditional clothing she wore in Istanbul. She only wore burkas and covered her face only when she went to the mosque with Abu on Fridays and at family gatherings, choosing to instead wear salwar kameez and letting loose her glittering dark brown hair that she always kept hidden in a bun inside her burka. I had only seen her face fully after returning to Pakistan and started appreciating the roundness of her face, the shine of her coiffed hair, and her full, plump lips. It seemed as though Ammi was growing more beautiful by the day when we got to Lahore. She attracted stares from the prying eyes of the people in the neighborhood when she went out by herself. Some, however, raised eyebrows and whispered among themselves from the rooftops and balconies, vilifying her and vilifying Bhutto at the same time.

“It hasn’t even been a couple weeks since Benazir came to power, and some women have already started thinking they can do anything,” Daadi declared sullenly when Ammi had started refusing to wear burka. “Haye Allah, what days are we seeing!”

Three years later, when I was in the eighth standard, Ammi received a letter in the mail. It was delivered one Monday morning when she and I were on our way to meet Noor’s betrothed at a restaurant at Fort Road in Shahi Mohalla in the Walled City. We were both dressed in our best clothing. I wore a set of corduroy pants and flannel shirt with red and black stripes, and Ammi donned a parrot-green pair of salwar kameez embroidered with stones and zari and form-fitting sandals with block heels, clutching a small leather tote bag in her hand. After signing the letter that had Abbu’s name printed at the top, she smiled gracefully, ran into her room, and safely deposited the letter in between the pages of one of her photo albums in the bottom-most drawer of the dresser. I had never seen her smile so gracefully, for coming to Lahore had changed her gleeful personality after some months. She had become morose, inclined to give into her worst instincts. She would even pick fights with Daadi and spend long hours being on the phone, speaking with distant relatives and her friends from Punjab. When I asked her as to what the letter was about, she dismissed my question, telling me that we were running late to meet the Shahs, the family into which Noor was marrying.

Noor had just finished her Bachelor’s in Politics from Jawaharlal Nehru University and returned from Delhi to live with Daadi and Naana when we had moved back to Lahore. She had gotten many offers from many great families from Punjab, Karachi, Lahore, and Faisalabad, but she had denied all of the offers, despite Daadi’s best efforts to cajole her into marrying one of the Nawabs from Karachi, until she finally married Mustafa Khan and was sent off to Islamabad with him. However, there was only one person whom she loved and wanted to get betrothed to; he was Naseeruddin Shah. Noor had watched all of his films and gone to all of his movie screenings and media events when she lived in Delhi. The walls in her room bore pictures of Naseeruddin in all corners; there were posters of his photographs printed in color that were stamped in all corners of her room. A movie banner displaying him holding a heroine in his laps, stroking the tufts of hair that escaped from her hat with one of his hands, and caressing her bare thigh with the other was hung from a hook behind the door, so that picture only came into view when the door was shut, and Daadi and Naana never noticed its presence in her room.

Besides the letter and Noor’s engagement and wedding, there were more salient news that came our way in my eighth standard. Meridian was closing. The Turkish missionaries were leaving the country for good after the government had mandated to close down the school when an investigation found that the missionaries attempted to convert the Sunnis, who make up the majority of Muslims in Lahore, to Shia Islam. Their such effort had been ruled unconstitutional by the High Court of Pakistan, and the government had given them a period of two weeks to banish to Turkey. With that notice, Daadi and Naana forbade me from going to school, and Ammi and Mumtaz hired tutors for me and Imran to study privately in our homes within less than a week. The tutoring sessions took place in our house at the dinner table. Imran was escorted precisely at 9:00 every morning to our home by his chauffeur and spent a large chunk of his day with me, for Daadi always insisted that he eat dinner with us before being sent away for the night.

One day, when Ammi had left for the bazaar to buy grocery, Imran and I sneaked into her room, sifting through the photo albums, leaping through the dusty diaries in which my mother wrote in English about her life with excellent penmanship. We came across several photographs that Ammi had never shown to me, and I wondered if Abu or Daadi and Naana had seen those pictures. Some of those photographs were of her dressed in short flared skirts, crop tops, spandex-like tights, lacey shirts, and knee-high boots with men who held her in their laps, caressing her body, fingers trailing across her thighs. Many of those men were dressed in high waisted jeans, denim jackets, plain loose shirts, and oversized blazers. Most of the pictures, I figured, were taken in nightclubs or discos and small parlors. In the background, some men and women were kissing each other, their lips pressed together. Others could be seen holding wine glasses and small glasses with transparent liquids in them and smoking cigars. Imran was absolutely flabbergasted to see those pictures, but I felt a strong sense of resentment at her for keeping those photographs from me. I knew Ammi harbored secrets, for she had taken to being conspicuously furtive by going out during the evenings without so much as letting us know where, having long conversations in English with her friends abroad from the phone booth in the foyer when everyone in the house had fallen asleep, and posting letters to friends abroad that she never spoke of. She had also started receiving letters, but the ones that Imran and I found were directed to Abu, and all of them were sealed as though never opened. We safely tucked the diaries, letters, and photo albums into the drawers where we had found them and went into my room.

That moment was when I had suddenly noticed that Imran’s voice had gotten huskier, his shoulders had broadened, his jawlines were more pronounced, and he had grown taller than me. I felt a sudden longing to touch him, to feel his body against mine, and to kiss him the way the men in the pictures we had just seen had kissed the women swinging one hand around their hips, holding the women tight against their muscular bodies.

“Kareem, what are you thinking of?” said Imran, shaking me off from my thoughts, gingerly touching my cheeks and staring into my eyes. “Do you wanna go watch TV?”

“Umm.. nothing,” I said, stuttering and stumbling with my words. “I was actually thinking of going to the movies. Ammi hasn’t takes us to the movies in such a long time. I was thinking if your Ammi could take us there next Sunday.”

“You silly goose,” he said, drawing me closer to him. “I think we should go to the movies too, but I also wonder what it would feel like to kiss you.”

“What do you mean?” I blurted out quickly. I always had a premonition that Imran was capable of wielding magic, that he possessed the power of foresight, but at that moment my conviction only bolstered, and I really wondered if Imran had been reading my mind all this time. “Haye Allah, you can read minds!” I gasped.

He grabbed hold of my arm and swung it around his hips, pulled me even closer, and at once locked his lips against mine, deftly working his tongue around and inside my lips. I could taste the scrumptiousness of the mango juice that he had during lunch on his tongue and feel the warm breath his mouth expelled. After some minutes, I broke free from his clasp and closed the door of my room, which had remained ajar while we were making out. I didn’t want him to stop there. I wanted him to caress my body and kiss my cheeks, my temples, my hands, my chest, and thigs. In turn, I also wanted to feel the muscular build of his body, his broad shoulders, and the bulge inside his pants. Imran developed an erection, and he rubbed it against the parting of my buttocks, penetrating inside my body. I moaned and gasped in sharp pain, and he instantly withdrew himself. For the rest of the hour, we were curled up in my bed, fondling each other’s body and incessantly kissing as though there were no tomorrow. After resolution, we showered together and went downstairs to continue our lessons.

Two days later, Ammi, in the middle of her meal, went upstairs to her room and came rushing down the stairs, tucking a letter into her armpit. She flashed the letter to Daadi and Naana and slowly divulged the jarring news to our family at the dinner table that we had secured a lottery to settle permanently in the U.S., and that we were leaving for Karachi for an interview the following day. When Ammi initially said that “we” had secured a lottery, I thought she meant all of us — Daadi, Naana, Noor, her husband, and the three of us — but only me, Abbu, and Ammi were going to America as I later came to know.

Naana stood from the table and stormed upstairs to his room without uttering a word, abandoning the food that Daadi had just served on his platter. A shudder went through Daadi, and she looked down at her own plate on the table, averting Ammi’s gaze. She finished eating her meal, and then spoke from her seat at the table.

“Aliya, what do you mean? You cannot just go around blurting out whatever you fancy,” said Daadi, sitting upright and somber. “Please apologize. Irfan’s Abu got upset and he left without even finishing his meal.”

“Ammi, actually, I have been wanting to tell you guys this, but Begum Aliya is right,” Abu told Daadi. “We have been thinking about this for quite some time. Given the current political situation of Pakistan, it wouldn’t be prudent of us to raise our children here.”

“Children?” Daadi gasped. “Allah! Allah! I pray to you every day, but why didn’t you take me to you before I witnessed this day?”

“Begum Aliya is expecting another child. We found out about that recently. We were planning to tell you all of this at some point.”

Abu and Ammi had already discussed the matters together as soon as the notice came, and Abu drove Ammi and I to the office of the American Consulate in Karachi for an interview the next day. Within two months, another letter came in the mail, letting us know that the Consulate had granted us Visas, and it was only a matter of time before tickets were booked, suitcases packed anew, and we left for America. When Imran came for visit the following day, I told him about the news that Ammi and Abu had thrust upon me and Daadi and Naana abruptly. Imran broke into tears, crying without restraint, when I told him the news. I knew how much the news pained him, for the thought of leaving Imran had made me sob and wince in pain for the whole night.

On the day we left Lahore for America, I could feel my grandparents mustering all of their courage in my presence to hold back tears from their blood-flecked eyes at breakfast. However, ceding to lamentation at our leaving, they broke into tears. I had never seen them cry before. Daadi wrapped me in her Pashmina shawl, kissing me in the cheeks and forehead. Tears streaming down her eyes stained the collars of my shirt. Naana didn’t come out of the house when we left, but I darted inside the house for the last time to bid him good-bye and hug him. I could feel the roundness of his potbelly as he enveloped me in a tight, convulsive hug, as though he would have never let go of me if he could. He did let go of me, however, and he handed me his dark-brown fez made from the wool of Persian lambs as a keepsake. I bid him farewell and darted out of the room to the front lawn, dragging my clothes-laden suitcase and meticulously clutching my passport and ticket with one hand. There was a throng of neighbors and relatives who had gathered by the main gate to bid us adieu. Imran was there amid the crowd. He flashed a quick big smile when he saw me appear in the lawn and came running toward me, embracing me for the last time before we would see each other again. I felt the rigidness of his built, his supple, moistened skin, and the citrus smell of his body, absorbing the crevices of his face into the depths of my memory.

I looked over my shoulders to scan the image of the house I called home permanently in my memory in fear of winding up like a neighbor who had gone to America and forgotten everything about his past, but at once, I mulled over and resented my parents’ decision to give my sister, who was yet to be born, and I a chance at a good life and education at the expense of letting my grandparents fend for themselves: what righteous fix were we chasing by leaving behind our withered and grief-beaten in a land wreaked by constant political turmoil to settle and build life anew from scratch on a faraway land? I had never seen my grandparents and Imran cry this way before. I felt sick to my stomach and unbearable agony at the sight of those three indomitable heroes of my childhood suffer a breakdown as we hopped on a van and bid adieu to the people gathered on the porch. I sobbed as I looked out the rolled-down window, and their bodies dissolved into thin air as the van whizzed by slowly through the congested street and into the Walled City of Lahore.

Within about 7 hours of flight, Ammi told me that we had landed in America, but I did not believe it. America was a nation situated all the way on the other side of the world. We could not have crossed the Atlantic so quickly. Plus, there hadn’t been a layover. There’s no mode of transportation — not even airplane — that traverses the Atlantic and the Middle East straight from Lahore to America. Her eyes could not meet mine when she told me so, and I sensed it in Ammi’s eyes instantly that she was concealing something from me. We had arrived in Istanbul, Turkey. Istanbul must have been the place of transit, I thought. However, Ammi and Abu went to the baggage claim area, waiting for the carousel to expel our luggage. I sat in a nearby armchair opposite the carousel. Abu and Ammi were among many of the passengers heaping their suitcases from the carousel, then gliding them against the shiny, tile-laden floors of the airport premises. I offered to help, but Abu and Ammi denied it — they always thought of me as brittle and delicate for mine was a body that never put on any shape or muscles, and Abu and Ammi frequently attributed that to my not eating enough, going on rants lauding Imran’s body and forcing me to eat more halal meat and biryanis and fruits than my stomach would allow. I was not very savvy then about navigating my ways at the airport; after all, it had been eight years since I had last been at an airport and flown on an aircraft. That was 1993. Still, I was baffled by the grandeur of airports and the constant stream of people in motion.

Ammi and I followed Abu’s lead, and he led us through the customs and into the observation deck. One woman, clad in dark burka and dark long gown, was frantically waving at us as we emerged into the observation deck after passing through metal detectors and having our luggage and other portable items run through the conveyor belts that checked for items that posed imminent threat. Not just that, but our bodies were also examined and prodded like cattle. Abu said that all airports around the world had levelled up their security screenings by leaps and bounds “after what happened.” I wasn’t quite sure what he meant by that, but before I could utter a word to ask him, the woman who waved at us now emerged in front of us, staring up and down our bodies in trance as though she had undergone a sudden moment of epiphany. After staring back into her eyes, for it was the only part of her body that one could see bare besides her hands, I felt a pang of nostalgia.

“Aliya Jaan, I have missed you so much,” the woman clasped my mother’s hands, speaking with a strong command of English. “I am so happy that we can now be friends again after all that we went through.” Ammi reached for a hug, but the woman gently pushed her away, showing restraint. “Now is not a good time,” the woman quickly responded. “If any security personnel or police officers see us engaging in any display of affection, we will be in deep trouble. They will not think twice before handcuffing us and shoving us into jail.” Her eye gravitated toward me, finally taking notice of my presence beside Ammi. “Aman Tanrım! Look at you, Kareem! You have grown so much — almost as tall as your Abu!”

“Fatma, we are so glad to see you, too,” Ammi replied. “Everything feels so different these days, though. The world has changed. And yes, Kareem has grown up so much.”

Fatma Dogan! Öğretmen Fatma! Voila! Fatma had come to retrieve us at the airport. Her husband had been waiting for us inside his Jeep at the parking lot by one of the terminals across from the exit. We were off to America — that is what Abu and Ammi had told everyone. I reasoned that Abu and Ammi must have thought of paying a visit to Fatma to revive and relive old memories, and that Fatma’s husband would drop us back at the airport after a couple hours, by when we would catch another flight to New York or California, after a scrumptious Turkish meal in their apartment. Much to my chagrin, however, Abu and Fatma’s husband heaped our luggage to their apartment, opening them and rummaging through the neatly folded stacks of clothing.

“Why did we bring our luggage upstairs to the apartment? Aren’t we going back to the airport again soon?” I asked the dreaded questions that had simmered and boiled inside of me since the moment my eyes crossed Fatma waving from the observation deck at the airport. There was an abrupt silence, and an expression of horror tinged with shock passed through Abu and Ammi’s faces. Maybe, it had dawned on them at that instance that they hadn’t told me the truth all this time. Maybe they couldn’t bear the thought of letting me know the truth that they had deferred my dreams after promising me the vagaries of American life — that they would have me enrolled me in one of the top-notch schools in America, where I would learn to play baseball with white friends; that they would arrange a tour of New York City, where I would see the Statue of Liberty and the poem inscribed on which draws everyone from all avenues of the world to America’s shores; that they would take me to concerts featuring Metallica and Nirvana, rendering me the opportunity to witness live performances by the bands whom I had grown so fond of in those days.

“Kareem, actually, the thing is that — ” Abu divulged, clearing his throat. “We should have told you this earlier. We were planning to travel to America, but our Visas have been revoked because of what happened, so we decided to move to Turkey instead.”

I had sensed it all along — from the moment Ammi told me we had arrived in America — that Abu and Ammi were lying to me about something, about going to America, but any shred of hope that I clung to that such would not be the case was instantly snuffed out when those words tumbled out of Abu’s mouth.

On September 11, just a week before our flight, a commercial passenger jet — American Airlines Flight 11 from Boston that was hijacked by terrorists — had crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center, tearing a gaping hole in the edifice and setting it on fire. A second hijacked airliner, Flight 175 from Boston, had crashed into the south tower at 9:03 a.m. American time. At 10:05, the south tower had fallen in a massive cloud of dust and debris, and at 10:28, the north tower had collapsed from the top down as if it were being peeled apart, releasing a tremendous cloud of debris and smoke. I did not know that I had memorized the precise details of what had befallen America, but how could I have not when the newspapers and all television channels had broadcast the news and the ghastly imagery of a city devastated by unfathomable attacks worldwide, and when the whole world was besieged by the incident that unfolded in New York City — to me a foreign territory all the way across the Atlantic in another part of the world that didn’t seem to bear any semblance of my life — sending shockwaves rippling through all parts of the world within minutes of the incident’s unfolding. Towers were burning, skyscrapers set on fire. Soot-filled office workers were desperately fleeing the area of attack, climbing out of rubbles, clinging steadfast to life, fighting the fires and flames that trapped them between the skyscrapers and rubbles.

The attack was one of terrorism. The American Congress, President, media, and intelligence had been quick to flame the fuels of anti-Brown and anti-Muslim sentiments, some even deeming all brown people liable for the incident that was carried out and orchestrated by one rogue group of rebels, whom America itself brought to power. The word “Muslim” had become a hated word. Brown-skinned people were deemed enemies of the American people, perpetual foreigners who deserved nothing but America’s contempt and hate. Word had gone round our mohalla in Lahore of one of our neighbors’ son, who was studying history in New York University, who had been spat at, beaten with an inch of his life, and shot to death by his own white friends, who had suddenly turned against him, having the audacity to kill their beloved brown friend, propelled by their unprecedented patriotism and love of America. Malaika Hussein, Abu’s friend’s sister, who was due to leave for San Francisco, on September 2nd, 2001, had her Visa revoked the day the incident happened — hers was another American dream deferred. How could I not have known that Daadi and Naana and Imran were sobbing in tears not because we left for America, a land fertile with seeds of freedom and opportunities, but one where people like us were deemed enemies, slaughtered in the light of day without any acknowledgement of our death?! How could I have not paid heed to the neighbors and uncles and aunties who counselled against traversing the treacherous waters of Atlantic and building life anew in the precarious shores of America?! How could I have been so hopeful about America, despite knowing that the land itself was a nation built on false promises and paradoxes?!

Fatma had arranged for us to stay with her for a week until we found our own apartment, carving out a space for me to sleep in one corner of the living room. I wanted to scream, sob, unleash all the tension that this news had created inside me, but I feigned nonchalance and obliged to drink the scorching Darjelling tea — the taste of which was always too strong for me to ever consume after my first cup of it — by Fatma, burning my tongue. The burn didn’t subside quickly, and I let out a grunt of anger, kicking at the lamp stand by my side, causing the tea cup perched on the stand to fall on the floor, spilling all over the carpet Abu’s favorite citrus-flavored tea, which stained the carpet beyond the point of cleaning it back to its pristine state. Time seemed frozen in Istanbul, where I laid on the makeshift bed on the floor, inaudibly crying the entire night, remembering Imran and the taste of his lips and tongue, while life in Lahore and America wore on.