h2>Dating : The Last Days of The Old Man

When Clay looked up from the notebook, the sky was starting to glow gray with new sun. By his watch, it was nearly thirteen hours since he had first flopped onto the bed and begun to read the notebook. He closed it and held it up in front of him, examining its spine and edges. It was not thick. It was about the size of a typical spiral notebook, yet Clay had not, in all that time, read the same page twice. The pages, written in Merle’s tight, angular cursive, more like sword strokes than pen strokes, read like a diary. What followed that first entry were recipes for a hundred different potions, concoctions, and draughts, hand-drawn diagrams of runic and totally alien symbols and designs, incantations, and passages in languages that Clay not only could not understand, but could not identify, with scripts totally alien to his concept of written language. These things were interspersed with dated diary entries from the first one in 1920 until October 1923, mostly dealing with subsequent attempts to escape from the library but occasionally with fending off an attack on The Point by various deities and mages. The entries just stopped with no apparent resolution. I see why nobody published this, Clay thought, but still, he had been fascinated. In fact, he had been so fascinated that he could still remember the pages of the book with a strange clarity, like in old movies when somebody would roll through microfilm in a library.

By the time Clay had his clothes on, the sun had risen up over the treetops and was baking hot. This is what he imagined it to be like inside a cremation oven, yellow, oppressive, persistent. By the time he parked the Nova in his spot on the street, the air was wavering with the heat.

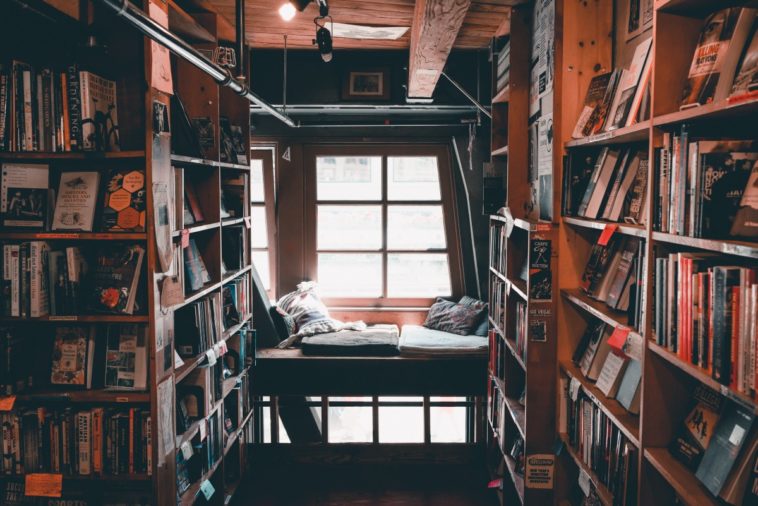

The door to the bookshop was shut and locked. He could see through the glass that the lights were out. Odd for this time of morning, Clay thought with some concern. Merle always propped the door open at first light. He said it gave the place the chance to air out before customers started showing up. Of course the place never really aired out, and there were no customers, but Clay never made these points. He pulled the keys out of his pocket, found the big silver one that opened up the shop and pulled the door open. An invisible cloud of hot air bubbled out of the shop and hit Clay in the face.

“Shit,” Clay said out loud, then he called out into the shop. If the air conditioner failed in the middle of the night, the old man could be in real trouble. “Merle?”

There was no answer. The place wasn’t large, but the walls and shelves of books muffled sound so well that it was possible for someone to yell from the door and not be heard in the back. Clay toed the metal doorstop down against the pavement and propped the door open. He shot his hand out to the right and flicked the light switch without looking. “Merle?” he called again for good measure. Still nothing. He took the center path through the store, heading straight for the counter at the back. He stepped behind the counter. He’d check the bathroom, Merle’s room, and the alleyway out back. Maybe the old man stepped out for a smoke.

Nothing. The store was deserted. As he came out of the back room where Merle slept, Clay caught sight of the silhouetted figure of a tall, thin man framed in the propped open front door. Clay stopped. “Help you?” he said.

“I know its early,” the man said in a silky, quiet voice that did not seem powerful enough to travel the full depth of the shop. “Are you open?”

“We open at eight,” said Clay. “We’re still setting up.” He turned toward the alley door and found himself rooted to the spot.

The tall man’s boots double-thunked on the hardwood floor of the shop with every step. He slowly strolled up to the counter, absently perusing the books on the shelves to either side of him as he approached.

“Can I help you?” Clay repeated with a grunt, trying and failing to lift his foot from the floor.

“I’m looking for something specific,” said the tall man. “Something not,” he paused thoughtfully, inserting no filler words into his speech, then “not mass produced.”

“What’s on the shelves is what we’ve got,” said Clay, forcing his voice into a disaffected tone, hoping to play the bored employee long enough so the man would leave and then maybe he could move, could continue his search for Merle.

The tall man finally arrived at the counter and dropped both long-fingered hands casually on the bar top. Clay noticed he was tall as he approached, but now that they were less than two feet away from each other, he was stunned at the man’s height. How had he fit through the front door without ducking? He must be at least seven feet tall, standing head and shoulders above Clay. He wore a slick black suit, exquisitely tailored so that it seemed to move as a part of him. His face was pale and gaunt but not old, and his eyes were sunken and dark. He looked around and clucked his tongue as though deciding what to order from a menu board.

“I’m looking for,” said the man, dragging out his syllables as if toying with Clay, “something called On The Nature of Magic. It’s an odd volume. Only one copy ever produced, in fact, and I believe it was written by the proprietor of this shop. Young man, have you heard of it?” On the last sentence, the man ceased looking around him and focused his black eyes on Clay’s brown ones.

“Not sure I know what you mean,” said Clay, who attempted to mock calm but spoke in a slightly higher register than usual. “If you come back later when the old man is here, I’ll bet he can help.”

The tall man chuckled and it sounded like dry leaves rustling. “Old man,” he said, shaking his head and looking down at the bar top. “Boy, you have no idea.”

“What’s your name?” Clay asked.

“Excuse me?” said the tall man, raising his eyes.

“Can I get your name? For when he gets back. So I can tell him you came by.”

“Giddeon,” said the man. “Arthur Giddeon. Actually, the old man and I have already had one chat this morning. He seemed to think that he had sent the book beyond my reach. Laughable old idiot. I have come here for the book and I intend to leave with it. I also intend to make it worth your while.” Giddeon tapped his long, pale fingers on the counter. One-two-three-four. One-two-three-four.

A jerk of recognition wanted to pull Clay’s face into a surprised expression. Giddeon. That was the name of one of the mages in the book that had tried to attack The Point. No, Clay thought. “Look, Mr. Giddeon,” he said, putting on his best Taco-bell-employee bored expression, “I don’t know what you’re talking about, and if Merle didn’t give you the book this morning, I don’t know what to tell you. Now if you don’t mind, I’ve got to finish opening up the store. We open at eight if you want to buy something else.”

Clay felt his airway constrict, and his feet lifted off the ground and he was floating up toward the ceiling. He looked, wide-eyed, at Giddeon whose eyes were rolled back into his head so that only the whites were showing. He was making a strange gesture with his right hand, his bony fingers bent out of their natural shapes. Clay felt himself bump into the ceiling of the shop. His hands were forced out to his sides and held fast against the rafters as if tied. He opened his mouth and closed it like a fish in dry air.

Giddeon spoke gruffly, through clenched teeth. “Show me where the book is now, boy, or I will turn you inside out like a plastic bag.”

Clay’s vision was starting to waver and darken at the edges, and his lungs were screaming. Without thinking about it, the book was suddenly flashed through his brain, spinning and landing on random pages like microfilm. Clay found that he could read them. There, that one, he thought. With the last bit of his air and strength, he made a gagging sound with his throat, like he was trying to speak. Instantly the pressure on his windpipe released, but he stayed firmly pinned to the ceiling.

“You wish to say something?” Giddeon said from the floor.

“Yes,” said Clay, hoarse, in between deep gasps of air. “I was trying to say that… you should not have… given me… your name.”

Giddeon’s eyes widened, and he forced his hand into an even more contorted gesture, but before he could do what he was planning, Clay recalled the page he wanted from the book, his eyes rolled back into his skull, and a gust of wind swept around the shop, scattering loose paper from underneath the counter and blowing books off shelves. Giddeon’s eyes rolled back down so that the black irises could again be seen and he dropped his hands, clearly expecting Clay to fall. Clay, however, stayed put, floating on the ceiling, and, now that his hands were freed, held them out in front of him and, gesturing toward Giddeon he twisted them both into odd, painful shapes. He mumbled something under his breath in a strange language. Then, much more loudly he said the word “Giddeon.”

A blast of air shot from the back of the shop and hit Giddeon in the torso like a battering ram, lifting him off his feet and throwing him the length of the shop and through the propped-open front door. Clay swiped his right hand through the air and the door slammed and the deadbolt turned. He floated down to the floor and set himself down, allowing his eyes to roll back into place and his hands and fingers to return to their normal resting shapes. The wind still circling the shop died down and then stopped. Merle’s gonna kill me for this mess, Clay thought and laughed out loud at himself.

He pivoted on his right foot and ran for the back door that lead to the alley. He grabbed the knob and hit the door with his shoulder so that it banged open loudly against the brick back wall. There, sitting propped against the blue, rusting dumpster, was Merle. He was bleeding from a wound in his stomach and his shirt was soaked in it. His eyes were closed, but when Clay began to approach, he opened them, but they were tired, half-lidded. “You read the book,” said Merle, “or you’d be as dead as I am.”

“Jesus fuck, Merle,” Clay said, squatting down next to the old man. “What is going on?”

“Put some hoo-doo on it so you’d remember what you read,” Merle said, mostly mumbling. “Did it work?” He wasn’t looking right at Clay anymore but over his shoulder at the sky.

“Yeah, Merle,” said Clay, “I’d say it did.”

The corners of Merle’s mouth turned up and his eyelids sagged in relief. He raised his hand and pointed past Clay to the other end of the alley. “Then you’ll know who that piece of shit is.”

Clay spun and saw Giddeon, limping, bleeding from one temple, round the corner of the building and step onto the gravel of the alley. Clay stood and pivoted to face him, holding his arms out to either side as if to protect Merle. “Stay away from us,” he yelled and it echoed in the alley.

Giddeon stopped twenty yards away. “Do you think I am afraid of a dying old man and his intern?” he said.

“Maybe you ought to be,” said Clay. Behind him, Merle let out a dry chuckle that turned into a wet cough.

“You don’t sound too good, old man,” said Giddeon. His boots crunched in the gravel as he slowly approached.

“Stay where you are,” Clay said, annunciating each word as though it were its own sentence.

“Make me,” said Giddeon with a twittering laugh.

“Boy,” said Merle softly, and he kicked Clay’s ankle with the toe of his boot. “You got a smoke?”

Clay, who was scrolling through the book in his head looking for something useful, looked over his shoulder at the old man. “Now, Merle?”

“Pretty sure I’m gonna be dead in a minute,” Merle said. “Now or never.”

Clay reached into his shirt pocket and pulled out the pack of Pall Malls and tossed them to Merle. The pack landed on the old man’s chest.

Clay turned his attention back to Giddeon and contorted his fingers. The wind picked up. This one will have to do again, Clay thought. I’ve got no time to keep looking. This time, though, Giddeon was ready. The wind that blasted down the alley did not even ruffle his suit. A steel trash can tumbled toward him and he deflected it with a wave of his hand. “The first time was a lucky shot, boy,” Giddeon said. “Now you’re just pissing me off.”

Clay heard the clink of Merle’s lighter behind him, then felt himself being gently pushed to one side by something he could not see. His sneakers scooted sideways, leaving trails in the gravel. He looked behind him and saw Merle getting painfully to his feet. “That’s alright, boy,” the old man said. “I’ve got one more in me.”

Giddeon laughed like he had never seen anything funnier. For a moment Clay was convinced he would fall on his back gasping with it.

Merle took a long drag of the Pall Mall and held the smoke in his lungs as he dropped the butt on the ground and stubbed it with his toe. His eyes rolled back and he brought his hands out in front of him and clapped once and it felt like a shockwave emanated from his hands and sure enough every pane of glass in every window in the alleyway shattered outward. Then Merle opened his mouth in an O shape and an animal growl escaped his throat. For a moment smoke drifted out of his mouth in lazy tendrils, then the air in front of his face wavered with heat and a stream of fire emerged from his lips like a military flamethrower, widening out in a cone that was five feet wide at its terminus, where it enveloped Giddeon completely. Clay could do nothing but listen to the screams and shield his eyes from the white-hot flames.

The flames stopped. Merle staggered backward and fell, landing on his ass and hitting his head hard on the steel dumpster which rang like an out-of-tune bell. A spurt of blood fell out of his soot-caked lips. He gestured for Clay to come over to him, but the boy was already sliding through the gravel next to him like a runner making a play for home plate. Clay skidded to a stop.

“Merle, that was crazy,” he said.

“Got the idea from you yesterday,” Merle said and grinned, showing blackened teeth. “Smaug the Mighty.”

An involuntary ha jumped out of Clay’s throat. “Are you gonna be alright?”

“Nope,” said Merle. “No, this is it for me, boy.”

Clay pulled his phone out of his pocket and dialed 9, but Merle put a hand on his wrist to stop him. “No, boy.”

“What, Merle? We’ve got to get you to a doctor.” Clay was breathing quick, shallow.

“Ain’t no doctor gonna fix what’s wrong with me,” said Merle. “And to be true, I don’t want them to. I’ve been waiting a long time to rest, and now I can.”

“Because of me,” said Clay. “Why me? Why did you give me the book? Why am I special?”

“You ain’t,” said Merle and he let out another wet cough. “But neither was I. We was both just there. Wrong place or right place, doesn’t matter. Only thing that matters now is what you do with it. To my mind, you’ve got work to do.”

“The Point,” Clay murmered.

“Yup,” said Merle. “Giddeon ain’t the only one after it, and they’ll split the Earth open to get it. Will you…” his voice faltered, his eyes going unfocussed, dialating. “Will you…” Merle’s head lolled to one side. His mouth hung slack. The hand on Clay’s wrist felt suddenly heavier.

A sob rose up in Clay’s throat, but he pushed it back down. He had work to do.